Imperative Programming

This chapter includes contributions from Jason Hickey.

Most of the code shown so far in this book, and indeed, most OCaml code in general, is pure. Pure code works without mutating the program’s internal state, performing I/O, reading the clock, or in any other way interacting with changeable parts of the world. Thus, a pure function behaves like a mathematical function, always returning the same results when given the same inputs, and never affecting the world except insofar as it returns the value of its computation. Imperative code, on the other hand, operates by side effects that modify a program’s internal state or interact with the outside world. An imperative function has a new effect, and potentially returns different results, every time it’s called.

Pure code is the default in OCaml, and for good reason—it’s generally easier to reason about, less error prone and more composable. But imperative code is of fundamental importance to any practical programming language, because real-world tasks require that you interact with the outside world, which is by its nature imperative. Imperative programming can also be important for performance. While pure code is quite efficient in OCaml, there are many algorithms that can only be implemented efficiently using imperative techniques.

OCaml offers a happy compromise here, making it easy and natural to program in a pure style, but also providing great support for imperative programming. This chapter will walk you through OCaml’s imperative features, and help you use them to their fullest.

Example: Imperative Dictionaries

We’ll start with the implementation of a simple imperative dictionary, i.e., a mutable mapping from keys to values. This is very much a toy implementation, and it’s really not suitable for any real-world use. That’s fine, since both Base and the standard library provide effective imperative dictionaries. There’s more advice on using Base’s implementation in particular in Chapter 14, Maps And Hash Tables.

The dictionary we’ll describe now, like those in Base and the standard library, will be implemented as a hash table. In particular, we’ll use an open hashing scheme, where the hash table will be an array of buckets, each bucket containing a list of key/value pairs that have been hashed into that bucket.

Here’s the signature we’ll match, provided as an interface file, dictionary.mli. The type ('a, 'b) t represents a dictionary with keys of type 'a and data of type 'b.

open Base

type ('a, 'b) t

val create

: hash:('a -> int)

-> equal:('a -> 'a -> bool)

-> ('a, 'b) t

val length : ('a, 'b) t -> int

val add : ('a, 'b) t -> key:'a -> data:'b -> unit

val find : ('a, 'b) t -> 'a -> 'b option

val iter : ('a, 'b) t -> f:(key:'a -> data:'b -> unit) -> unit

val remove : ('a, 'b) t -> 'a -> unitThis mli also includes a collection of helper functions whose purpose and behavior should be largely inferable from their names and type signatures. Note that the create function takes as its arguments functions for hashing keys and testing them for equality.

You might notice that some of the functions, like add and iter, return unit. This is unusual for functional code, but common for imperative functions whose primary purpose is to mutate some data structure, rather than to compute a value.

We’ll now walk through the implementation (contained in the corresponding ml file, dictionary.ml) piece by piece, explaining different imperative constructs as they come up.

Our first step is to define the type of a dictionary as a record.

open Base

type ('a, 'b) t =

{ mutable length : int

; buckets : ('a * 'b) list array

; hash : 'a -> int

; equal : 'a -> 'a -> bool

}The first field, length, is declared as mutable. In OCaml, records are immutable by default, but individual fields are mutable when marked as such. The second field, buckets, is immutable but contains an array, which is itself a mutable data structure. The remaining fields contain the functions for hashing and equality checking.

Now we’ll start putting together the basic functions for manipulating a dictionary:

let num_buckets = 17

let hash_bucket t key = t.hash key % num_buckets

let create ~hash ~equal =

{ length = 0

; buckets = Array.create ~len:num_buckets []

; hash

; equal

}

let length t = t.length

let find t key =

List.find_map

t.buckets.(hash_bucket t key)

~f:(fun (key', data) ->

if t.equal key' key then Some data else None)Note that num_buckets is a constant, which means our bucket array is of fixed length. A practical implementation would need to be able to grow the array as the number of elements in the dictionary increases, but we’ll omit this to simplify the presentation.

The function hash_bucket is used throughout the rest of the module to choose the position in the array that a given key should be stored at.

The other functions defined above are fairly straightforward:

create- Creates an empty dictionary.

length- Grabs the length from the corresponding record field, thus returning the number of entries stored in the dictionary.

find- Looks for a matching key in the table and returns the corresponding value if found as an option.

Another important piece of imperative syntax shows up in find: we write array.(index) to grab a value from an array. find also uses List.find_map, which you can see the type of by typing it into the toplevel:

open Base;;

List.find_map;;

>- : 'a list -> f:('a -> 'b option) -> 'b option = <fun>

List.find_map iterates over the elements of the list, calling f on each one until a Some is returned by f, at which point that value is returned. If f returns None on all values, then None is returned.

Now let’s look at the implementation of iter:

let iter t ~f =

for i = 0 to Array.length t.buckets - 1 do

List.iter t.buckets.(i) ~f:(fun (key, data) -> f ~key ~data)

doneiter is designed to walk over all the entries in the dictionary. In particular, iter t ~f will call f for each key/value pair in dictionary t. Note that f must return unit, since it is expected to work by side effect rather than by returning a value, and the overall iter function returns unit as well.

The code for iter uses two forms of iteration: a for loop to walk over the array of buckets; and within that loop a call to List.iter to walk over the values in a given bucket. We could have done the outer loop with a recursive function instead of a for loop, but for loops are syntactically convenient, and are more familiar and idiomatic in imperative contexts.

The following code is for adding and removing mappings from the dictionary:

let bucket_has_key t i key =

List.exists t.buckets.(i) ~f:(fun (key', _) -> t.equal key' key)

let add t ~key ~data =

let i = hash_bucket t key in

let replace = bucket_has_key t i key in

let filtered_bucket =

if replace

then

List.filter t.buckets.(i) ~f:(fun (key', _) ->

not (t.equal key' key))

else t.buckets.(i)

in

t.buckets.(i) <- (key, data) :: filtered_bucket;

if not replace then t.length <- t.length + 1

let remove t key =

let i = hash_bucket t key in

if bucket_has_key t i key

then (

let filtered_bucket =

List.filter t.buckets.(i) ~f:(fun (key', _) ->

not (t.equal key' key))

in

t.buckets.(i) <- filtered_bucket;

t.length <- t.length - 1)This preceding code is made more complicated by the fact that we need to detect whether we are overwriting or removing an existing binding, so we can decide whether t.length needs to be changed. The helper function bucket_has_key is used for this purpose.

Another piece of syntax shows up in both add and remove: the use of the <- operator to update elements of an array (array.(i) <- expr) and for updating a record field (record.field <- expression).

We also use ;, the sequencing operator, to express a sequence of imperative actions. We could have done the same using let bindings:

let () = t.buckets.(i) <- (key, data) :: filtered_bucket in

if not replace then t.length <- t.length + 1but ; is more concise and idiomatic. More generally,

<expr1>;

<expr2>;

...

<exprN>is equivalent to

let () = <expr1> in

let () = <expr2> in

...

<exprN>When a sequence expression expr1; expr2 is evaluated, expr1 is evaluated first, and then expr2. The expression expr1 should have type unit (though this is a warning rather than a hard restriction. The -strict-sequence compiler flag makes this a hard restriction, which is generally a good idea), and the value of expr2 is returned as the value of the entire sequence. For example, the sequence print_string "hello world"; 1 + 2 first prints the string "hello world", then returns the integer 3.

Note also that we do all of the side-effecting operations at the very end of each function. This is good practice because it minimizes the chance that such operations will be interrupted with an exception, leaving the data structure in an inconsistent state.

Primitive Mutable Data

Now that we’ve looked at a complete example, let’s take a more systematic look at imperative programming in OCaml. We encountered two different forms of mutable data above: records with mutable fields and arrays. We’ll now discuss these in more detail, along with the other primitive forms of mutable data that are available in OCaml.

Array-Like Data

OCaml supports a number of array-like data structures; i.e., mutable integer-indexed containers that provide constant-time access to their elements. We’ll discuss several of them in this section.

Ordinary arrays

The array type is used for general-purpose polymorphic arrays. The Array module has a variety of utility functions for interacting with arrays, including a number of mutating operations. These include Array.set, for setting an individual element, and Array.blit, for efficiently copying values from one range of indices to another.

Arrays also come with special syntax for retrieving an element from an array:

<array_expr>.(<index_expr>)and for setting an element in an array:

<array_expr>.(<index_expr>) <- <value_expr>Out-of-bounds accesses for arrays (and indeed for all the array-like data structures) will lead to an exception being thrown.

Array literals are written using [| and |] as delimiters. Thus, [| 1; 2; 3 |] is a literal integer array.

bytes and strings.

The strings we’ve encountered thus far are essentially byte arrays, and are most often used for textual data. You could imagine using a char array (a char represents an 8-bit character) for the same purpose, but strings are considerably more space-efficient; an array uses one 8-byte word on a 64-bit machine—to store a single entry, whereas strings use one byte per character.

Unlike arrays, though, strings are immutable, and sometimes, it’s convenient to have a space-efficient, mutable array of bytes. Happily, OCaml has that, via the bytes type.

You can set individual characters using Bytes.set, and a value of type bytes can be converted to and from the string type.

let b = Bytes.of_string "foobar";;

>val b : bytes = "foobar"

Bytes.set b 0 (Char.uppercase (Bytes.get b 0));;

>- : unit = ()

Bytes.to_string b;;

>- : string = "Foobar"

Bigarrays

A Bigarray.t is a handle to a block of memory stored outside of the OCaml heap. These are mostly useful for interacting with C or Fortran libraries, and are discussed in Chapter 23, Memory Representation Of Values. Bigarrays too have their own getting and setting syntax:

<bigarray_expr>.{<index_expr>}

<bigarray_expr>.{<index_expr>} <- <value_expr>Mutable Record and Object Fields and Ref Cells

As we’ve seen, records are immutable by default, but individual record fields can be declared as mutable. These mutable fields can be set using the <- operator, i.e., record.field <- expr.

As we’ll see in Chapter 12, Objects, fields of an object can similarly be declared as mutable, and can then be modified in much the same way as record fields.

Ref cells

Variables in OCaml are never mutable—they can refer to mutable data, but what the variable points to can’t be changed. Sometimes, though, you want to do exactly what you would do with a mutable variable in another language: define a single, mutable value. In OCaml this is typically achieved using a ref, which is essentially a container with a single mutable polymorphic field.

The definition for the ref type is as follows:

type 'a ref = { mutable contents : 'a };;

>type 'a ref = { mutable contents : 'a; }

The standard library defines the following operators for working with refs.

ref expr- Constructs a reference cell containing the value defined by the expression

expr. !refcell- Returns the contents of the reference cell.

refcell := expr- Replaces the contents of the reference cell.

You can see these in action:

let x = ref 1;;

>val x : int ref = {Base.Ref.contents = 1}

!x;;

>- : int = 1

x := !x + 1;;

>- : unit = ()

!x;;

>- : int = 2

The preceding are just ordinary OCaml functions, which could be defined as follows:

let ref x = { contents = x };;

>val ref : 'a -> 'a ref = <fun>

let (!) r = r.contents;;

>val ( ! ) : 'a ref -> 'a = <fun>

let (:=) r x = r.contents <- x;;

>val ( := ) : 'a ref -> 'a -> unit = <fun>

This reflects the fact that ref cells are really just a special case of mutable record fields.

Foreign Functions

Another source of imperative operations in OCaml is resources that come from interfacing with external libraries through OCaml’s foreign function interface (FFI). The FFI opens OCaml up to imperative constructs that are exported by system calls or other external libraries. Many of these come built in, like access to the write system call or to the clock, while others come from user libraries. OCaml’s FFI is discussed in more detail in Chapter 22, Foreign Function Interface.

For and While Loops

OCaml provides support for traditional imperative looping constructs, in particular, for and while loops. Neither of these constructs is strictly necessary, since they can be simulated with recursive functions. Nonetheless, explicit for and while loops are both more concise and more idiomatic when programming imperatively.

The for loop is the simpler of the two. Indeed, we’ve already seen the for loop in action—the iter function in Dictionary is built using it. Here’s a simple example of for. Note that we open the Stdio library to get access to the printf function.

open Stdio;;

for i = 0 to 3 do printf "i = %d\n" i done;;

>i = 0

>i = 1

>i = 2

>i = 3

>- : unit = ()

As you can see, the upper and lower bounds are inclusive. We can also use downto to iterate in the other direction:

for i = 3 downto 0 do printf "i = %d\n" i done;;

>i = 3

>i = 2

>i = 1

>i = 0

>- : unit = ()

Note that the loop variable of a for loop, i in this case, is immutable in the scope of the loop and is also local to the loop, i.e., it can’t be referenced outside of the loop.

OCaml also supports while loops, which include a condition and a body. The loop first evaluates the condition, and then, if it evaluates to true, evaluates the body and starts the loop again. Here’s a simple example of a function for reversing an array in place:

let rev_inplace ar =

let i = ref 0 in

let j = ref (Array.length ar - 1) in

(* terminate when the upper and lower indices meet *)

while !i < !j do

(* swap the two elements *)

let tmp = ar.(!i) in

ar.(!i) <- ar.(!j);

ar.(!j) <- tmp;

(* bump the indices *)

Int.incr i;

Int.decr j

done;;

>val rev_inplace : 'a array -> unit = <fun>

let nums = [|1;2;3;4;5|];;

>val nums : int array = [|1; 2; 3; 4; 5|]

rev_inplace nums;;

>- : unit = ()

nums;;

>- : int array = [|5; 4; 3; 2; 1|]

In the preceding example, we used Int.incr and Int.decr, which are built-in functions for incrementing and decrementing an int ref by one, respectively.

Example: Doubly Linked Lists

Another common imperative data structure is the doubly linked list. Doubly linked lists can be traversed in both directions, and elements can be added and removed from the list in constant time. Core defines a doubly linked list (the module is called Doubly_linked), but we’ll define our own linked list library as an illustration.

Here’s the mli of the module we’ll build:

open Base

type 'a t

type 'a element

(** Basic list operations *)

val create : unit -> 'a t

val is_empty : 'a t -> bool

(** Navigation using [element]s *)

val first : 'a t -> 'a element option

val next : 'a element -> 'a element option

val prev : 'a element -> 'a element option

val value : 'a element -> 'a

(** Whole-data-structure iteration *)

val iter : 'a t -> f:('a -> unit) -> unit

val find_el : 'a t -> f:('a -> bool) -> 'a element option

(** Mutation *)

val insert_first : 'a t -> 'a -> 'a element

val insert_after : 'a element -> 'a -> 'a element

val remove : 'a t -> 'a element -> unitNote that there are two types defined here: 'a t, the type of a list; and 'a element, the type of an element. Elements act as pointers to the interior of a list and allow us to navigate the list and give us a point at which to apply mutating operations.

Now let’s look at the implementation. We’ll start by defining 'a element and 'a t:

open Base

type 'a element =

{ value : 'a

; mutable next : 'a element option

; mutable prev : 'a element option

}

type 'a t = 'a element option refAn 'a element is a record containing the value to be stored in that node as well as optional (and mutable) fields pointing to the previous and next elements. At the beginning of the list, the prev field is None, and at the end of the list, the next field is None.

The type of the list itself, 'a t, is a mutable reference to an optional element. This reference is None if the list is empty, and Some otherwise.

Now we can define a few basic functions that operate on lists and elements:

let create () = ref None

let is_empty t = Option.is_none !t

let value elt = elt.value

let first t = !t

let next elt = elt.next

let prev elt = elt.prevThese all follow relatively straightforwardly from our type definitions.

Cyclic Data Structures

Doubly linked lists are a cyclic data structure, meaning that it is possible to follow a nontrivial sequence of pointers that closes in on itself. In general, building cyclic data structures requires the use of side effects. This is done by constructing the data elements first, and then adding cycles using assignment afterward.

There is an exception to this, though: you can construct fixed-size cyclic data structures using let rec:

let rec endless_loop = 1 :: 2 :: 3 :: endless_loop;;

>val endless_loop : int list = [1; 2; 3; <cycle>]

This approach is quite limited, however. General-purpose cyclic data structures require mutation.

Modifying the List

Now, we’ll start considering operations that mutate the list, starting with insert_first, which inserts an element at the front of the list:

let insert_first t value =

let new_elt = { prev = None; next = !t; value } in

(match !t with

| Some old_first -> old_first.prev <- Some new_elt

| None -> ());

t := Some new_elt;

new_eltinsert_first first defines a new element new_elt, and then links it into the list, finally setting the list itself to point to new_elt. Note that the precedence of a match expression is very low, so to separate it from the following assignment (t := Some new_elt), we surround the match with parentheses. We could have used begin ... end for the same purpose, but without some kind of bracketing, the final assignment would incorrectly become part of the None case.

We can use insert_after to insert elements later in the list. insert_after takes as arguments both an element after which to insert the new node and a value to insert:

let insert_after elt value =

let new_elt = { value; prev = Some elt; next = elt.next } in

(match elt.next with

| Some old_next -> old_next.prev <- Some new_elt

| None -> ());

elt.next <- Some new_elt;

new_eltWe also need a remove function:

let remove t elt =

let { prev; next; _ } = elt in

(match prev with

| Some prev -> prev.next <- next

| None -> t := next);

(match next with

| Some next -> next.prev <- prev

| None -> ());

elt.prev <- None;

elt.next <- NoneNote that the preceding code is careful to change the prev pointer of the following element and the next pointer of the previous element, if they exist. If there’s no previous element, then the list pointer itself is updated. In any case, the next and previous pointers of the element itself are set to None.

These functions are more fragile than they may seem. In particular, misuse of the interface may lead to corrupted data. For example, double-removing an element will cause the main list reference to be set to None, thus emptying the list. Similar problems arise from removing an element from a list it doesn’t belong to.

This shouldn’t be a big surprise. Complex imperative data structures can be quite tricky, considerably trickier than their pure equivalents. The issues described previously can be dealt with by more careful error detection, and such error correction is taken care of in modules like Core’s Doubly_linked. You should use imperative data structures from a well-designed library when you can. And when you can’t, you should make sure to put great care into your error handling.

Iteration Functions

When defining containers like lists, dictionaries, and trees, you’ll typically want to define a set of iteration functions like iter, map, and fold, which let you concisely express common iteration patterns.

Dlist has two such iterators: iter, the goal of which is to call a unit-producing function on every element of the list, in order; and find_el, which runs a provided test function on each value stored in the list, returning the first element that passes the test. Both iter and find_el are implemented using simple recursive loops that use next to walk from element to element and value to extract the element from a given node:

let iter t ~f =

let rec loop = function

| None -> ()

| Some el ->

f (value el);

loop (next el)

in

loop !t

let find_el t ~f =

let rec loop = function

| None -> None

| Some elt -> if f (value elt) then Some elt else loop (next elt)

in

loop !tThis completes our implementation, but there’s still considerably more work to be done to make a really usable doubly linked list. As mentioned earlier, you’re probably better off using something like Core Doubly_linked module that has a more complete interface and has more of the tricky corner cases worked out. Nonetheless, this example should serve to demonstrate some of the techniques you can use to build nontrivial imperative data structure in OCaml, as well as some of the pitfalls.

Laziness and Other Benign Effects

There are many instances where you basically want to program in a pure style, but you want to make limited use of side effects to improve the performance of your code. Such side effects are sometimes called benign effects, and they are a useful way of leveraging OCaml’s imperative features while still maintaining most of the benefits of pure programming.

One of the simplest benign effects is laziness. A lazy value is one that is not computed until it is actually needed. In OCaml, lazy values are created using the lazy keyword, which can be used to convert any expression of type s into a lazy value of type s lazy_t. The evaluation of that expression is delayed until forced with Lazy.force:

let v = lazy (print_endline "performing lazy computation"; Float.sqrt 16.);;

>val v : float lazy_t = <lazy>

Lazy.force v;;

>performing lazy computation

>- : float = 4.

Lazy.force v;;

>- : float = 4.

You can see from the print statement that the actual computation was performed only once, and only after force had been called.

To better understand how laziness works, let’s walk through the implementation of our own lazy type. We’ll start by declaring types to represent a lazy value:

type 'a lazy_state =

| Delayed of (unit -> 'a)

| Value of 'a

| Exn of exn;;

>type 'a lazy_state = Delayed of (unit -> 'a) | Value of 'a | Exn of exn

type 'a our_lazy = { mutable state : 'a lazy_state };;

>type 'a our_lazy = { mutable state : 'a lazy_state; }

A lazy_state represents the possible states of a lazy value. A lazy value is Delayed before it has been run, where Delayed holds a function for computing the value in question. A lazy value is in the Value state when it has been forced and the computation ended normally. The Exn case is for when the lazy value has been forced, but the computation ended with an exception. A lazy value is simply a record with a single mutable field containing a lazy_state, where the mutability makes it possible to change from being in the Delayed state to being in the Value or Exn states.

We can create a lazy value from a thunk, i.e., a function that takes a unit argument. Wrapping an expression in a thunk is another way to suspend the computation of an expression:

let our_lazy f = { state = Delayed f };;

>val our_lazy : (unit -> 'a) -> 'a our_lazy = <fun>

let v =

our_lazy (fun () ->

print_endline "performing lazy computation"; Float.sqrt 16.);;

>val v : float our_lazy = {state = Delayed <fun>}

Now we just need a way to force a lazy value. The following function does just that.

let our_force l =

match l.state with

| Value x -> x

| Exn e -> raise e

| Delayed f ->

try

let x = f () in

l.state <- Value x;

x

with exn ->

l.state <- Exn exn;

raise exn;;

>val our_force : 'a our_lazy -> 'a = <fun>

Which we can use in the same way we used Lazy.force:

our_force v;;

>performing lazy computation

>- : float = 4.

our_force v;;

>- : float = 4.

The main user-visible difference between our implementation of laziness and the built-in version is syntax. Rather than writing our_lazy (fun () -> sqrt 16.), we can (with the built-in lazy) just write lazy (sqrt 16.), avoiding the necessity of declaring a function.

Memoization and Dynamic Programming

Another benign effect is memoization. A memoized function remembers the result of previous invocations of the function so that they can be returned without further computation when the same arguments are presented again.

Here’s a function that takes as an argument an arbitrary single-argument function and returns a memoized version of that function. Here we’ll use Base’s Hashtbl module, rather than our toy Dictionary.

This implementation requires an argument of a Hashtbl.Key.t, which plays the role of the hash and equal from Dictionary. Hashtbl.Key.t is an example of what’s called a first-class module, which we’ll see more of in Chapter 11, First Class Modules.

let memoize m f =

let memo_table = Hashtbl.create m in

(fun x ->

Hashtbl.find_or_add memo_table x ~default:(fun () -> f x));;

>val memoize : 'a Hashtbl.Key.t -> ('a -> 'b) -> 'a -> 'b = <fun>

The preceding code is a bit tricky. memoize takes as its argument a function f and then allocates a polymorphic hash table (called memo_table), and returns a new function which is the memoized version of f. When called, this new function uses Hashtbl.find_or_add to try to find a value in the memo_table, and if it fails, to call f and store the result. Note that memo_table is referred to by the function, and so won’t be collected until the function returned by memoize is itself collected.

Memoization can be useful whenever you have a function that is expensive to recompute and you don’t mind caching old values indefinitely. One important caution: a memoized function by its nature leaks memory. As long as you hold on to the memoized function, you’re holding every result it has returned thus far.

Memoization is also useful for efficiently implementing some recursive algorithms. One good example is the algorithm for computing the edit distance (also called the Levenshtein distance) between two strings. The edit distance is the number of single-character changes (including letter switches, insertions, and deletions) required to convert one string to the other. This kind of distance metric can be useful for a variety of approximate string-matching problems, like spellcheckers.

Consider the following code for computing the edit distance. Understanding the algorithm isn’t important here, but you should pay attention to the structure of the recursive calls:

let rec edit_distance s t =

match String.length s, String.length t with

| (0,x) | (x,0) -> x

| (len_s,len_t) ->

let s' = String.drop_suffix s 1 in

let t' = String.drop_suffix t 1 in

let cost_to_drop_both =

if Char.(=) s.[len_s - 1] t.[len_t - 1] then 0 else 1

in

List.reduce_exn ~f:Int.min

[ edit_distance s' t + 1

; edit_distance s t' + 1

; edit_distance s' t' + cost_to_drop_both

];;

>val edit_distance : string -> string -> int = <fun>

edit_distance "OCaml" "ocaml";;

>- : int = 2

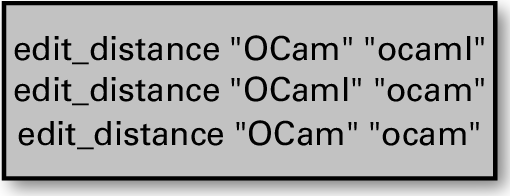

The thing to note is that if you call edit_distance "OCaml" "ocaml", then that will in turn dispatch the following calls:

And these calls will in turn dispatch other calls:

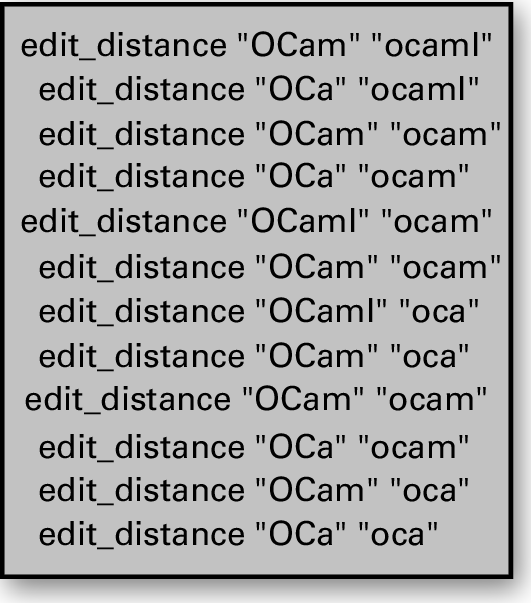

As you can see, some of these calls are repeats. For example, there are two different calls to edit_distance "OCam" "oca". The number of redundant calls grows exponentially with the size of the strings, meaning that our implementation of edit_distance is brutally slow for large strings. We can see this by writing a small timing function, using Core’s Time module.

let time f =

let open Core in

let start = Time.now () in

let x = f () in

let stop = Time.now () in

printf "Time: %F ms\n" (Time.diff stop start |> Time.Span.to_ms);

x;;

>val time : (unit -> 'a) -> 'a = <fun>

And now we can use this to try out some examples:

time (fun () -> edit_distance "OCaml" "ocaml");;

>Time: 0.655651092529 ms

>- : int = 2

time (fun () -> edit_distance "OCaml 4.13" "ocaml 4.13");;

>Time: 2541.6533947 ms

>- : int = 2

Just those few extra characters made it thousands of times slower!

Memoization would be a huge help here, but to fix the problem, we need to memoize the calls that edit_distance makes to itself. Such recursive memoization is closely related to a common algorithmic technique called dynamic programming, except that with dynamic programming, you do the necessary sub-computations bottom-up, in anticipation of needing them. With recursive memoization, you go top-down, only doing a sub-computation when you discover that you need it.

To see how to do this, let’s step away from edit_distance and instead consider a much simpler example: computing the nth element of the Fibonacci sequence. The Fibonacci sequence by definition starts out with two 1s, with every subsequent element being the sum of the previous two. The classic recursive definition of Fibonacci is as follows:

let rec fib i =

if i <= 1 then i else fib (i - 1) + fib (i - 2);;

>val fib : int -> int = <fun>

This is, however, exponentially slow, for the same reason that edit_distance was slow: we end up making many redundant calls to fib. It shows up quite dramatically in the performance:

time (fun () -> fib 20);;

>Time: 1.14369392395 ms

>- : int = 6765

time (fun () -> fib 40);;

>Time: 14752.7184486 ms

>- : int = 102334155

As you can see, fib 40 takes thousands of times longer to compute than fib 20.

So, how can we use memoization to make this faster? The tricky bit is that we need to insert the memoization before the recursive calls within fib. We can’t just define fib in the ordinary way and memoize it after the fact and expect the first call to fib to be improved.

let fib = memoize (module Int) fib;;

>val fib : int -> int = <fun>

time (fun () -> fib 40);;

>Time: 18174.5970249 ms

>- : int = 102334155

time (fun () -> fib 40);;

>Time: 0.00524520874023 ms

>- : int = 102334155

In order to make fib fast, our first step will be to rewrite fib in a way that unwinds the recursion. The following version expects as its first argument a function (called fib) that will be called in lieu of the usual recursive call.

let fib_norec fib i =

if i <= 1 then i

else fib (i - 1) + fib (i - 2);;

>val fib_norec : (int -> int) -> int -> int = <fun>

We can now turn this back into an ordinary Fibonacci function by tying the recursive knot:

let rec fib i = fib_norec fib i;;

>val fib : int -> int = <fun>

fib 20;;

>- : int = 6765

We can even write a polymorphic function that we’ll call make_rec that can tie the recursive knot for any function of this form:

let make_rec f_norec =

let rec f x = f_norec f x in

f;;

>val make_rec : (('a -> 'b) -> 'a -> 'b) -> 'a -> 'b = <fun>

let fib = make_rec fib_norec;;

>val fib : int -> int = <fun>

fib 20;;

>- : int = 6765

This is a pretty strange piece of code, and it may take a few moments of thought to figure out what’s going on. Like fib_norec, the function f_norec passed in to make_rec is a function that isn’t recursive but takes as an argument a function that it will call. What make_rec does is to essentially feed f_norec to itself, thus making it a true recursive function.

This is clever enough, but all we’ve really done is find a new way to implement the same old slow Fibonacci function. To make it faster, we need a variant of make_rec that inserts memoization when it ties the recursive knot. We’ll call that function memo_rec:

let memo_rec m f_norec x =

let fref = ref (fun _ -> assert false) in

let f = memoize m (fun x -> f_norec !fref x) in

fref := f;

f x;;

>val memo_rec : 'a Hashtbl.Key.t -> (('a -> 'b) -> 'a -> 'b) -> 'a -> 'b =

> <fun>

Note that memo_rec has almost the same signature as make_rec.

We’re using the reference here as a way of tying the recursive knot without using a let rec, which for reasons we’ll describe later wouldn’t work here.

Using memo_rec, we can now build an efficient version of fib:

let fib = memo_rec (module Int) fib_norec;;

>val fib : int -> int = <fun>

time (fun () -> fib 40);;

>Time: 0.121355056763 ms

>- : int = 102334155

As you can see, the exponential time complexity is now gone.

The memory behavior here is important. If you look back at the definition of memo_rec, you’ll see that the call memo_rec fib_norec does not trigger a call to memoize. Only when fib is called and thereby the final argument to memo_rec is presented does memoize get called. The result of that call falls out of scope when the fib call returns, and so calling memo_rec on a function does not create a memory leak—the memoization table is collected after the computation completes.

We can use memo_rec as part of a single declaration that makes this look like it’s little more than a special form of let rec:

let fib = memo_rec (module Int) (fun fib i ->

if i <= 1 then 1 else fib (i - 1) + fib (i - 2));;

>val fib : int -> int = <fun>

Memoization is overkill for implementing Fibonacci, and indeed, the fib defined above is not especially efficient, allocating space linear in the number passed into fib. It’s easy enough to write a Fibonacci function that takes a constant amount of space.

But memoization is a good approach for optimizing edit_distance, and we can apply the same approach we used on fib here. We will need to change edit_distance to take a pair of strings as a single argument, since memo_rec only works on single-argument functions. (We can always recover the original interface with a wrapper function.) With just that change and the addition of the memo_rec call, we can get a memoized version of edit_distance. The memoization key is going to be a pair of strings, so we need to get our hands on a module with the necessary functionality for building a hash-table in Base.

Writing hash-functions and equality tests and the like by hand can be tedious and error prone, so instead we’ll use a few different syntax extensions for deriving the necessary functionality automatically. By enabling ppx_jane, we pull in a collection of such derivers, three of which we use in defining String_pair below.

#require "ppx_jane";;

module String_pair = struct

type t = string * string [@@deriving sexp_of, hash, compare]

end;;

>module String_pair :

> sig

> type t = string * string

> val sexp_of_t : t -> Sexp.t

> val hash_fold_t : Hash.state -> t -> Hash.state

> val hash : t -> int

> val compare : t -> t -> int

> end

With that in hand, we can define our optimized form of edit_distance.

let edit_distance = memo_rec (module String_pair)

(fun edit_distance (s,t) ->

match String.length s, String.length t with

| (0,x) | (x,0) -> x

| (len_s,len_t) ->

let s' = String.drop_suffix s 1 in

let t' = String.drop_suffix t 1 in

let cost_to_drop_both =

if Char.(=) s.[len_s - 1] t.[len_t - 1] then 0 else 1

in

List.reduce_exn ~f:Int.min

[ edit_distance (s',t ) + 1

; edit_distance (s ,t') + 1

; edit_distance (s',t') + cost_to_drop_both

]);;

>val edit_distance : String_pair.t -> int = <fun>

This new version of edit_distance is much more efficient than the one we started with; the following call is many thousands of times faster than it was without memoization.

time (fun () -> edit_distance ("OCaml 4.09","ocaml 4.09"));;

>Time: 0.964403152466 ms

>- : int = 2

Limitations of let rec

You might wonder why we didn’t tie the recursive knot in memo_rec using let rec, as we did for make_rec earlier. Here’s code that tries to do just that:

let memo_rec m f_norec =

let rec f = memoize m (fun x -> f_norec f x) in

f;;

>Line 2, characters 17-49:

>Error: This kind of expression is not allowed as right-hand side of `let rec'

OCaml rejects the definition because OCaml, as a strict language, has limits on what it can put on the right-hand side of a let rec. In particular, imagine how the following code snippet would be compiled:

let rec x = x + 1Note that x is an ordinary value, not a function. As such, it’s not clear how this definition should be handled by the compiler. You could imagine it compiling down to an infinite loop, but x is of type int, and there’s no int that corresponds to an infinite loop. As such, this construct is effectively impossible to compile.

To avoid such impossible cases, the compiler only allows three possible constructs to show up on the right-hand side of a let rec: a function definition, a constructor, or the lazy keyword. This excludes some reasonable things, like our definition of memo_rec, but it also blocks things that don’t make sense, like our definition of x.

It’s worth noting that these restrictions don’t show up in a lazy language like Haskell. Indeed, we can make something like our definition of x work if we use OCaml’s laziness:

let rec x = lazy (force x + 1);;

>val x : int lazy_t = <lazy>

Of course, actually trying to compute this will fail. OCaml’s lazy throws an exception when a lazy value tries to force itself as part of its own evaluation.

force x;;

>Exception: Lazy.Undefined.

But we can also create useful recursive definitions with lazy. In particular, we can use laziness to make our definition of memo_rec work without explicit mutation:

let lazy_memo_rec m f_norec x =

let rec f = lazy (memoize m (fun x -> f_norec (force f) x)) in

(force f) x;;

>val lazy_memo_rec : 'a Hashtbl.Key.t -> (('a -> 'b) -> 'a -> 'b) -> 'a -> 'b =

> <fun>

time (fun () -> lazy_memo_rec (module Int) fib_norec 40);;

>Time: 0.181913375854 ms

>- : int = 102334155

Laziness is more constrained than explicit mutation, and so in some cases can lead to code whose behavior is easier to think about.

Input and Output

Imperative programming is about more than modifying in-memory data structures. Any function that doesn’t boil down to a deterministic transformation from its arguments to its return value is imperative in nature. That includes not only things that mutate your program’s data, but also operations that interact with the world outside of your program. An important example of this kind of interaction is I/O, i.e., operations for reading or writing data to things like files, terminal input and output, and network sockets.

There are multiple I/O libraries in OCaml. In this section we’ll discuss OCaml’s buffered I/O library that can be used through the In_channel and Out_channel modules in Stdio. Other I/O primitives are also available through the Unix module in Core as well as Async, the asynchronous I/O library that is covered in Chapter 16, Concurrent Programming With Async. Most of the functionality in Core’s In_channel and Out_channel (and in Core’s Unix module) derives from the standard library, but we’ll use Core’s interfaces here.

Terminal I/O

OCaml’s buffered I/O library is organized around two types: in_channel, for channels you read from, and out_channel, for channels you write to. The In_channel and Out_channel modules only have direct support for channels corresponding to files and terminals; other kinds of channels can be created through the Unix module.

We’ll start our discussion of I/O by focusing on the terminal. Following the UNIX model, communication with the terminal is organized around three channels, which correspond to the three standard file descriptors in Unix:

In_channel.stdin- The “standard input” channel. By default, input comes from the terminal, which handles keyboard input.

Out_channel.stdout- The “standard output” channel. By default, output written to

stdoutappears on the user terminal. Out_channel.stderr- The “standard error” channel. This is similar to

stdoutbut is intended for error messages.

The values stdin, stdout, and stderr are useful enough that they are also available in the top level of Core’s namespace directly, without having to go through the In_channel and Out_channel modules.

Let’s see this in action in a simple interactive application. The following program, time_converter, prompts the user for a time zone, and then prints out the current time in that time zone. Here, we use Core’s Zone module for looking up a time zone, and the Time module for computing the current time and printing it out in the time zone in question:

open Core

let () =

Out_channel.output_string stdout "Pick a timezone: ";

Out_channel.flush stdout;

match In_channel.(input_line stdin) with

| None -> failwith "No timezone provided"

| Some zone_string ->

let zone = Time_unix.Zone.find_exn zone_string in

let time_string = Time.to_string_abs (Time.now ()) ~zone in

Out_channel.output_string stdout

(String.concat

["The time in ";Time_unix.Zone.to_string zone;" is ";time_string;".\n"]);

Out_channel.flush stdoutWe can build this program using dune and run it, though you’ll need to add a dune-project and dune file, as described in Chapter 4, Files Modules and Programs. You’ll see that it prompts you for input, as follows:

$ dune exec ./time_converter.exe

Pick a timezone:You can then type in the name of a time zone and hit Return, and it will print out the current time in the time zone in question:

Pick a timezone: Europe/London

The time in Europe/London is 2013-08-15 00:03:10.666220+01:00.We called Out_channel.flush on stdout because out_channels are buffered, which is to say that OCaml doesn’t immediately do a write every time you call output_string. Instead, writes are buffered until either enough has been written to trigger the flushing of the buffers, or until a flush is explicitly requested. This greatly increases the efficiency of the writing process by reducing the number of system calls.

Note that In_channel.input_line returns a string option, with None indicating that the input stream has ended (i.e., an end-of-file condition). Out_channel.output_string is used to print the final output, and Out_channel.flush is called to flush that output to the screen. The final flush is not technically required, since the program ends after that instruction, at which point all remaining output will be flushed anyway, but the explicit flush is nonetheless good practice.

Formatted Output with printf

Generating output with functions like Out_channel.output_string is simple and easy to understand, but can be a bit verbose. OCaml also supports formatted output using the printf function, which is modeled after printf in the C standard library. printf takes a format string that describes what to print and how to format it, as well as arguments to be printed, as determined by the formatting directives embedded in the format string. So, for example, we can write:

printf

"%i is an integer, %F is a float, \"%s\" is a string\n"

3 4.5 "five";;

>3 is an integer, 4.5 is a float, "five" is a string

>- : unit = ()

Unlike C’s printf, the printf in OCaml is type-safe. In particular, if we provide an argument whose type doesn’t match what’s presented in the format string, we’ll get a type error:

printf "An integer: %i\n" 4.5;;

>Line 1, characters 27-30:

>Error: This expression has type float but an expression was expected of type

> int

Understanding Format Strings

The format strings used by printf turn out to be quite different from ordinary strings. This difference ties to the fact that OCaml’s printf facility, unlike the equivalent in C, is type-safe. In particular, the compiler checks that the types referred to by the format string match the types of the rest of the arguments passed to printf.

To check this, OCaml needs to analyze the contents of the format string at compile time, which means the format string needs to be available as a string literal at compile time. Indeed, if you try to pass an ordinary string to printf, the compiler will complain:

let fmt = "%i is an integer\n";;

>val fmt : string = "%i is an integer\n"

printf fmt 3;;

>Line 1, characters 8-11:

>Error: This expression has type string but an expression was expected of type

> ('a -> 'b, Stdio.Out_channel.t, unit) format =

> ('a -> 'b, Stdio.Out_channel.t, unit, unit, unit, unit) format6

If OCaml infers that a given string literal is a format string, then it parses it at compile time as such, choosing its type in accordance with the formatting directives it finds. Thus, if we add a type annotation indicating that the string we’re defining is actually a format string, it will be interpreted as such. (Here, we open the CamlinternalFormatBasics so that the representation of the format string that’s printed out won’t fill the whole page.)

open CamlinternalFormatBasics;;

let fmt : ('a, 'b, 'c) format =

"%i is an integer\n";;

>val fmt : (int -> 'c, 'b, 'c) format =

> Format

> (Int (Int_i, No_padding, No_precision,

> String_literal (" is an integer\n", End_of_format)),

> "%i is an integer\n")

And accordingly, we can pass it to printf:

printf fmt 3;;

>3 is an integer

>- : unit = ()

If this looks different from everything else you’ve seen so far, that’s because it is. This is really a special case in the type system. Most of the time, you don’t need to know about this special handling of format strings—you can just use printf and not worry about the details. But it’s useful to keep the broad outlines of the story in the back of your head.

Now let’s see how we can rewrite our time conversion program to be a little more concise using printf:

open Core

let () =

printf "Pick a timezone: %!";

match In_channel.input_line In_channel.stdin with

| None -> failwith "No timezone provided"

| Some zone_string ->

let zone = Time_unix.Zone.find_exn zone_string in

let time_string = Time.to_string_abs (Time.now ()) ~zone in

printf "The time in %s is %s.\n%!" (Time_unix.Zone.to_string zone) time_stringIn the preceding example, we’ve used only two formatting directives: %s, for including a string, and %! which causes printf to flush the channel.

printf’s formatting directives offer a significant amount of control, allowing you to specify things like:

Alignment and padding

Escaping rules for strings

Whether numbers should be formatted in decimal, hex, or binary

Precision of float conversions

There are also printf-style functions that target outputs other than stdout, including:

eprintf, which prints tostderrfprintf, which prints to an arbitraryout_channelsprintf, which returns a formatted string

All of this, and a good deal more, is described in the API documentation for the Printf module in the OCaml Manual.

File I/O

Another common use of in_channels and out_channels is for working with files. Here are a couple of functions—one that creates a file full of numbers, and the other that reads in such a file and returns the sum of those numbers:

let create_number_file filename numbers =

let outc = Out_channel.create filename in

List.iter numbers ~f:(fun x -> Out_channel.fprintf outc "%d\n" x);

Out_channel.close outc;;

>val create_number_file : string -> int list -> unit = <fun>

let sum_file filename =

let file = In_channel.create filename in

let numbers = List.map ~f:Int.of_string (In_channel.input_lines file) in

let sum = List.fold ~init:0 ~f:(+) numbers in

In_channel.close file;

sum;;

>val sum_file : string -> int = <fun>

create_number_file "numbers.txt" [1;2;3;4;5];;

>- : unit = ()

sum_file "numbers.txt";;

>- : int = 15

For both of these functions, we followed the same basic sequence: we first create the channel, then use the channel, and finally close the channel. The closing of the channel is important, since without it, we won’t release resources associated with the file back to the operating system.

One problem with the preceding code is that if it throws an exception in the middle of its work, it won’t actually close the file. If we try to read a file that doesn’t actually contain numbers, we’ll see such an error:

sum_file "/etc/hosts";;

>Exception:

>(Failure

> "Int.of_string: \"127.0.0.1 localhost localhost.localdomain localhost4 localhost4.localdomain4\"")

And if we do this over and over in a loop, we’ll eventually run out of file descriptors:

for i = 1 to 10000 do try ignore (sum_file "/etc/hosts") with _ -> () done;;

>- : unit = ()

sum_file "numbers.txt";;

>Error: I/O error: ...: Too many open files

And now, you’ll need to restart your toplevel if you want to open any more files!

To avoid this, we need to make sure that our code cleans up after itself. We can do this using the protect function described in Chapter 7, Error Handling, as follows:

let sum_file filename =

let file = In_channel.create filename in

Exn.protect ~f:(fun () ->

let numbers = List.map ~f:Int.of_string (In_channel.input_lines file) in

List.fold ~init:0 ~f:(+) numbers)

~finally:(fun () -> In_channel.close file);;

>val sum_file : string -> int = <fun>

And now, the file descriptor leak is gone:

for i = 1 to 10000 do try ignore (sum_file "/etc/hosts" : int) with _ -> () done;;

>- : unit = ()

sum_file "numbers.txt";;

>- : int = 15

This is really an example of a more general issue with imperative programming and exceptions. If you’re changing the internal state of your program and you’re interrupted by an exception, you need to consider quite carefully if it’s safe to continue working from your current state.

In_channel has functions that automate the handling of some of these details. For example, In_channel.with_file takes a filename and a function for processing data from an in_channel and takes care of the bookkeeping associated with opening and closing the file. We can rewrite sum_file using this function, as shown here:

let sum_file filename =

In_channel.with_file filename ~f:(fun file ->

let numbers = List.map ~f:Int.of_string (In_channel.input_lines file) in

List.fold ~init:0 ~f:(+) numbers);;

>val sum_file : string -> int = <fun>

Another misfeature of our implementation of sum_file is that we read the entire file into memory before processing it. For a large file, it’s more efficient to process a line at a time. You can use the In_channel.fold_lines function to do just that:

let sum_file filename =

In_channel.with_file filename ~f:(fun file ->

In_channel.fold_lines file ~init:0 ~f:(fun sum line ->

sum + Int.of_string line));;

>val sum_file : string -> int = <fun>

This is just a taste of the functionality of In_channel and Out_channel. To get a fuller understanding, you should review the API documentation.

Order of Evaluation

The order in which expressions are evaluated is an important part of the definition of a programming language, and it is particularly important when programming imperatively. Most programming languages you’re likely to have encountered are strict, and OCaml is too. In a strict language, when you bind an identifier to the result of some expression, the expression is evaluated before the variable is bound. Similarly, if you call a function on a set of arguments, those arguments are evaluated before they are passed to the function.

Consider the following simple example. Here, we have a collection of angles, and we want to determine if any of them have a negative sin. The following snippet of code would answer that question:

let x = Float.sin 120. in

let y = Float.sin 75. in

let z = Float.sin 128. in

List.exists ~f:(fun x -> Float.O.(x < 0.)) [x;y;z];;

>- : bool = true

In some sense, we don’t really need to compute the sin 128 because sin 75 is negative, so we could know the answer before even computing sin 128.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Using the lazy keyword, we can write the original computation so that sin 128 won’t ever be computed:

let x = lazy (Float.sin 120.) in

let y = lazy (Float.sin 75.) in

let z = lazy (Float.sin 128.) in

List.exists ~f:(fun x -> Float.O.(Lazy.force x < 0.)) [x;y;z];;

>- : bool = true

We can confirm that fact by a few well-placed printfs:

let x = lazy (printf "1\n"; Float.sin 120.) in

let y = lazy (printf "2\n"; Float.sin 75.) in

let z = lazy (printf "3\n"; Float.sin 128.) in

List.exists ~f:(fun x -> Float.O.(Lazy.force x < 0.)) [x;y;z];;

>1

>2

>- : bool = true

OCaml is strict by default for a good reason: lazy evaluation and imperative programming generally don’t mix well because laziness makes it harder to reason about when a given side effect is going to occur. Understanding the order of side effects is essential to reasoning about the behavior of an imperative program.

Because OCaml is strict, we know that expressions that are bound by a sequence of let bindings will be evaluated in the order that they’re defined. But what about the evaluation order within a single expression? Officially, the answer is that evaluation order within an expression is undefined. In practice, OCaml has only one compiler, and that behavior is a kind of de facto standard. Unfortunately, the evaluation order in this case is often the opposite of what one might expect.

Consider the following example:

List.exists ~f:(fun x -> Float.O.(x < 0.))

[ (printf "1\n"; Float.sin 120.);

(printf "2\n"; Float.sin 75.);

(printf "3\n"; Float.sin 128.); ];;

>3

>2

>1

>- : bool = true

Here, you can see that the subexpression that came last was actually evaluated first! This is generally the case for many different kinds of expressions. If you want to make sure of the evaluation order of different subexpressions, you should express them as a series of let bindings.

Side Effects and Weak Polymorphism

Consider the following simple, imperative function:

let remember =

let cache = ref None in

(fun x ->

match !cache with

| Some y -> y

| None -> cache := Some x; x);;

>val remember : '_weak1 -> '_weak1 = <fun>

remember simply caches the first value that’s passed to it, returning that value on every call. That’s because cache is created and initialized once and is shared across invocations of remember.

remember is not a terribly useful function, but it raises an interesting question: what should its type be?

On its first call, remember returns the same value it’s passed, which means its input type and return type should match. Accordingly, remember should have type t -> t for some type t. There’s nothing about remember that ties the choice of t to any particular type, so you might expect OCaml to generalize, replacing t with a polymorphic type variable. It’s this kind of generalization that gives us polymorphic types in the first place. The identity function, as an example, gets a polymorphic type in this way:

let identity x = x;;

>val identity : 'a -> 'a = <fun>

identity 3;;

>- : int = 3

identity "five";;

>- : string = "five"

As you can see, the polymorphic type of identity lets it operate on values with different types.

This is not what happens with remember, though. As you can see from the above examples, the type that OCaml infers for remember looks almost, but not quite, like the type of the identity function. Here it is again:

val remember : '_weak1 -> '_weak1 = <fun>The underscore in the type variable '_weak1 tells us that the variable is only weakly polymorphic, which is to say that it can be used with any single type. That makes sense because, unlike identity, remember always returns the value it was passed on its first invocation, which means its return value must always have the same type.

OCaml will convert a weakly polymorphic variable to a concrete type as soon as it gets a clue as to what concrete type it is to be used as:

let remember_three () = remember 3;;

>val remember_three : unit -> int = <fun>

remember;;

>- : int -> int = <fun>

remember "avocado";;

>Line 1, characters 10-19:

>Error: This expression has type string but an expression was expected of type

> int

Note that the type of remember was settled by the definition of remember_three, even though remember_three was never called!

The Value Restriction

So, when does the compiler infer weakly polymorphic types? As we’ve seen, we need weakly polymorphic types when a value of unknown type is stored in a persistent mutable cell. Because the type system isn’t precise enough to determine all cases where this might happen, OCaml uses a rough rule to flag cases that don’t introduce any persistent mutable cells, and to only infer polymorphic types in those cases. This rule is called the value restriction.

The core of the value restriction is the observation that some kinds of expressions, which we’ll refer to as simple values, by their nature can’t introduce persistent mutable cells, including:

Constants (i.e., things like integer and floating-point literals)

Constructors that only contain other simple values

Function declarations, i.e., expressions that begin with

funorfunction, or the equivalent let binding,let f x = ...letbindings of the formletvar=expr1inexpr2, where bothexpr1andexpr2are simple values

Thus, the following expression is a simple value, and as a result, the types of values contained within it are allowed to be polymorphic:

(fun x -> [x;x]);;

>- : 'a -> 'a list = <fun>

But, if we write down an expression that isn’t a simple value by the preceding definition, we’ll get different results.

identity (fun x -> [x;x]);;

>- : '_weak2 -> '_weak2 list = <fun>

In principle, it would be safe to infer a fully polymorphic variable here, but because OCaml’s type system doesn’t distinguish between pure and impure functions, it can’t separate those two cases.

The value restriction doesn’t require that there is no mutable state, only that there is no persistent mutable state that could share values between uses of the same function. Thus, a function that produces a fresh reference every time it’s called can have a fully polymorphic type:

let f () = ref None;;

>val f : unit -> 'a option ref = <fun>

But a function that has a mutable cache that persists across calls, like memoize, can only be weakly polymorphic.

Partial Application and the Value Restriction

Most of the time, when the value restriction kicks in, it’s for a good reason, i.e., it’s because the value in question can actually only safely be used with a single type. But sometimes, the value restriction kicks in when you don’t want it. The most common such case is partially applied functions. A partially applied function, like any function application, is not a simple value, and as such, functions created by partial application are sometimes less general than you might expect.

Consider the List.init function, which is used for creating lists where each element is created by calling a function on the index of that element:

List.init;;

>- : int -> f:(int -> 'a) -> 'a list = <fun>

List.init 10 ~f:Int.to_string;;

>- : string list = ["0"; "1"; "2"; "3"; "4"; "5"; "6"; "7"; "8"; "9"]

Imagine we wanted to create a specialized version of List.init that always created lists of length 10. We could do that using partial application, as follows:

let list_init_10 = List.init 10;;

>val list_init_10 : f:(int -> '_weak3) -> '_weak3 list = <fun>

As you can see, we now infer a weakly polymorphic type for the resulting function. That’s because there’s nothing that guarantees that List.init isn’t creating a persistent ref somewhere inside of it that would be shared across multiple calls to list_init_10. We can eliminate this possibility, and at the same time get the compiler to infer a polymorphic type, by avoiding partial application:

let list_init_10 ~f = List.init 10 ~f;;

>val list_init_10 : f:(int -> 'a) -> 'a list = <fun>

This transformation is referred to as eta expansion and is often useful to resolve problems that arise from the value restriction.

Relaxing the Value Restriction

OCaml is actually a little better at inferring polymorphic types than was suggested previously. The value restriction as we described it is basically a syntactic check: you can do a few operations that count as simple values, and anything that’s a simple value can be generalized.

But OCaml actually has a relaxed version of the value restriction that can make use of type information to allow polymorphic types for things that are not simple values.

For example, we saw that a function application, even a simple application of the identity function, is not a simple value and thus can turn a polymorphic value into a weakly polymorphic one:

identity (fun x -> [x;x]);;

>- : '_weak4 -> '_weak4 list = <fun>

But that’s not always the case. When the type of the returned value is immutable, then OCaml can typically infer a fully polymorphic type:

identity [];;

>- : 'a list = []

On the other hand, if the returned type is mutable, then the result will be weakly polymorphic:

[||];;

>- : 'a array = [||]

identity [||];;

>- : '_weak5 array = [||]

A more important example of this comes up when defining abstract data types. Consider the following simple data structure for an immutable list type that supports constant-time concatenation:

module Concat_list : sig

type 'a t

val empty : 'a t

val singleton : 'a -> 'a t

val concat : 'a t -> 'a t -> 'a t (* constant time *)

val to_list : 'a t -> 'a list (* linear time *)

end = struct

type 'a t = Empty | Singleton of 'a | Concat of 'a t * 'a t

let empty = Empty

let singleton x = Singleton x

let concat x y = Concat (x,y)

let rec to_list_with_tail t tail =

match t with

| Empty -> tail

| Singleton x -> x :: tail

| Concat (x,y) -> to_list_with_tail x (to_list_with_tail y tail)

let to_list t =

to_list_with_tail t []

end;;

>module Concat_list :

> sig

> type 'a t

> val empty : 'a t

> val singleton : 'a -> 'a t

> val concat : 'a t -> 'a t -> 'a t

> val to_list : 'a t -> 'a list

> end

The details of the implementation don’t matter so much, but it’s important to note that a Concat_list.t is unquestionably an immutable value. However, when it comes to the value restriction, OCaml treats it as if it were mutable:

Concat_list.empty;;

>- : 'a Concat_list.t = <abstr>

identity Concat_list.empty;;

>- : '_weak6 Concat_list.t = <abstr>

The issue here is that the signature, by virtue of being abstract, has obscured the fact that Concat_list.t is in fact an immutable data type. We can resolve this in one of two ways: either by making the type concrete (i.e., exposing the implementation in the mli), which is often not desirable; or by marking the type variable in question as covariant. We’ll learn more about covariance and contravariance in Chapter 12, Objects, but for now, you can think of it as an annotation that can be put in the interface of a pure data structure.

In particular, if we replace type 'a t in the interface with type +'a t, that will make it explicit in the interface that the data structure doesn’t contain any persistent references to values of type 'a, at which point, OCaml can infer polymorphic types for expressions of this type that are not simple values:

module Concat_list : sig

type +'a t

val empty : 'a t

val singleton : 'a -> 'a t

val concat : 'a t -> 'a t -> 'a t (* constant time *)

val to_list : 'a t -> 'a list (* linear time *)

end = struct

type 'a t = Empty | Singleton of 'a | Concat of 'a t * 'a t

let empty = Empty

let singleton x = Singleton x

let concat x y = Concat (x,y)

let rec to_list_with_tail t tail =

match t with

| Empty -> tail

| Singleton x -> x :: tail

| Concat (x,y) -> to_list_with_tail x (to_list_with_tail y tail)

let to_list t =

to_list_with_tail t []

end;;

>module Concat_list :

> sig

> type +'a t

> val empty : 'a t

> val singleton : 'a -> 'a t

> val concat : 'a t -> 'a t -> 'a t

> val to_list : 'a t -> 'a list

> end

Now, we can apply the identity function to Concat_list.empty without losing any polymorphism:

identity Concat_list.empty;;

>- : 'a Concat_list.t = <abstr>

Summary

This chapter has covered quite a lot of ground, including:

Discussing the building blocks of mutable data structures as well as the basic imperative constructs like

forloops,whileloops, and the sequencing operator;Walking through the implementation of a couple of classic imperative data structures

Discussing so-called benign effects like memoization and laziness

Covering OCaml’s API for blocking I/O

Discussing how language-level issues like order of evaluation and weak polymorphism interact with OCaml’s imperative features

The scope and sophistication of the material here is an indication of the importance of OCaml’s imperative features. The fact that OCaml defaults to immutability shouldn’t obscure the fact that imperative programming is a fundamental part of building any serious application, and that if you want to be an effective OCaml programmer, you need to understand OCaml’s approach to imperative programming.